FAQ - Groundwater Quantity

I’ve always heard people say that there are oceans of water down there. Is that true?

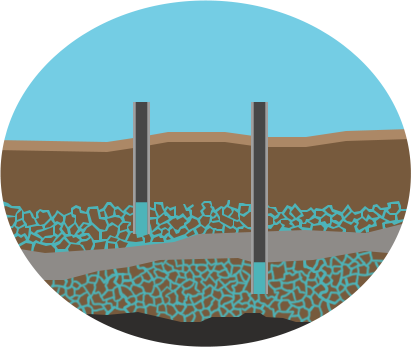

Not really, although it’s a lovely vision. Groundwater is hosted in both unconfined shallow aquifers and confined bedrock aquifers. The distribution of these water-bearing units in the subsurface is directly related to the geologic history of the region. And frequently, the geology is quite complicated. You might have an unconfined aquifer inset into a bedrock aquifer such that some wells yield 500 gallons per minute (gpm), but a well a mile away only yields 5 gpm. Even within a rock unit, there can be a lot of variation in rock type throughout the thickness of the unit. This means you could have mudstone in one area, but move over 100 feet and have a nice sandstone aquifer. Also, the thickness of various aquifer units can vary quite a bit regionally. This makes it really tricky to understand where your groundwater is and how much you have.

I’m worried that my neighbor’s new well will cause my well to go dry. How do I know if this will happen?

The geology that hosts our groundwater systems is quite complicated. Sometimes you are indeed drawing from the same aquifer as your neighbor. If their well is significantly deeper than yours, and they draw on it, they can produce a cone of depression that will pull the water table down below the bottom of your well. However, sometimes two wells that are close together are actually in different aquifers, either because the rock type has changed between wells or because one well has been drilled much deeper into a different aquifer unit that is separated from shallower aquifers by an aquitard (an impermeable rock layer that acts as a barrier to flow). If you notice your well’s behavior changes significantly when your neighbor is using their well, that can be a sign that they are connected. It’s a good idea to try to understand the local hydrogeology to determine if you’re in the same or different aquifer units. Sometimes wells go dry because the local aquifer they were drawing from has simply become too depleted to use: this may not necessarily be because of a nearby well being used.

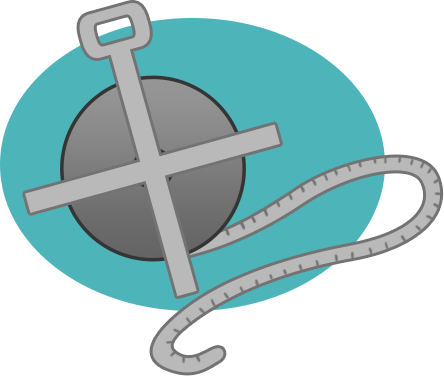

How do you measure a well?

We use either a measuring tape or a pressure transducer (also called a data logger). If we’re measuring the depth to the water in a well with a tape, we use a graduated steel tape that is thin enough to slip past pumps, tubing, safety lines, sucker rods and other things that might be in your well. If the well is empty, we can also use an e-tape that has a probe on the end of it. This type of measurement provides a spot reading of the depth to water at that well. If this measurement is taken twice a year (summer and winter) over several years, we can see a pattern in the behavior of a local water table over time. Pressure transducers are small instruments that are installed in the well and can be programmed to take a reading every day. These provide a much more detailed history of the water table over time.

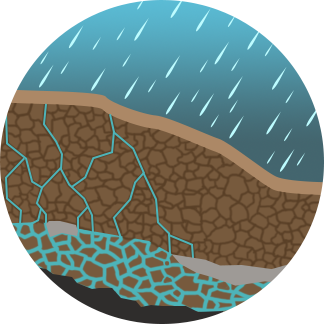

How can you tell if my groundwater is recharging?

We can use two different data sets to help determine if your local water table can recover if there’s significant precipitation in your area: static water levels and tritium isotopes. By measuring static water levels over several years, we can gain some understanding of how your local water table behaves. If it is constantly declining, even when you get a good rain or snow year, that’s a sign that precipitation is either taking a long time to percolate down to the water table or it is not reaching the water table at all. Tritium, an isotope of hydrogen, was released in large quantities during atomic bomb testing in the 1950s. So if there is measurable tritium in your groundwater, it indicates that post-1950s water is making its way into the aquifer system. However, tritium does not indicate the quantity of recharge, just that there is some entering your local water table.

What do I do if I learn that my water table is not recharging?

First off, it’s important to remember that your aquifer may indeed recharge, but recharge may be so slow that, on a human time scale, the use of water greatly exceeds what is being replaced. For agricultural operations, it is all about conserving every drop! For farming, consider crop type and growing season. As an example, some farmers in northeastern New Mexico have begun experimenting with a type of sileage corn that has a very short growing season so that they are watering for less time each year than they might for higher grade corn varieties. Other folks have switched to low water crops, and some are transitioning to dryland farming (with cover crops!). Ranchers have begun converting windmills to solar-driven pumps or submersible pumps on timers. Adding a float valve and/or shade balls to your drinker can also help with conservation. For windmills, shutting them off as soon as cattle are moved from a pasture saves water, although it may increase maintenance costs for leather replacement.

How do I know where to drill a new well?

This is a very tricky question. If you have an idea of the geology below your feet you can be somewhat better at predicting potential locations for a new well. But even that kind of information isn’t perfect, especially in places where the geology is complicated and the aquifers are partitioned into separate little “bathtubs.” There’s no guarantee that having geologic or hydrologic information at hand will give you the perfect location for a new well. Well drillers who are local to the area frequently have a good idea of where good water has been located and where dry holes tend to occur. Ideally, combining knowledge of your local hydrogeologist and well driller will give you your best potential spots. There are subsurface imaging techniques that can be used, but these are frequently very expensive and can be time-consuming to utilize...

Contact:

Kate Ziegler,

Ziegler Geologic Consulting, LLC